|

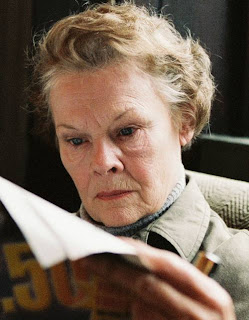

| You really shouldn't piss off a Dame; especially if she's Dame Judi Dench and the film is "Notes on a Scandal" |

I like my Judi Dench a little on the spooky side. Sure, she's salty in her Oscar winning mini-role as Elizabeth I in "Shakespeare in Love", flinty in "Mrs. Brown" and "Chocolat", and downright sweet in "Ladies in Lavender", but for my money, give me evil, scheming Dame Dench, and there's no better showcase for that than the 2006 release "Notes on a Scandal".

She's a vicious old dragon of a teacher in a London school, who fills her empty days and nights by writing endlessly in a series of diaries. A great deal of Dench's performance in the film is done in voice-over, narrating her character Barbara's interior monologues, and Dench's vocal abilities give them a sense of urgency and intimacy that we don't often get when characters thoughts are provided. It's obvious that Dench's decades of stage work have provided her with the actor's tools to play her voice on many levels, all of which she does remarkably well.

Befriending new teacher Sheba Hart (Cate Blanchett), Dench finds herself drawn to the younger woman, and actively seeks out her friendship. The suggestion of homoeroticism is there from the beginning, but then we think we are smarter than movies are and can figure them out ahead of time. Usually, we are, but with "Notes on a Scandal", things are never quite what they seem to be.

As the friendship between Barbara and Sheba develops, we see Barbara becoming watchful and nurturing towards her new youg friend, excited by all the possibilities of their companionship, which she can share with no one save her diaries. An invitation for luncheon at Sheba's home sends Barbara out to have her hair done, purchase a new outfit, and arrive at the door carrying flowers and a bottle of wine. In her mind, this is her first date with Sheba. Barbara's feelings about Sheba's husband and children leave little doubt that she considers herself and Sheba above the rest of them all, and that it is fate that their relationship continue to develop in the intense manner it already has.

So far, Barbara has seemed a bit creepy, but when she gets hold of a scandalous secret involving Sheba, the story really moves into gear. Telling Sheba that she must provide all the details to Barbara in order to keep them both safe, the younger woman does so, not realizing she is providing dangerous ammunition to someone like Barbara (I am convinced that Barbara is a Scorpio). Barbara uses this clandestine knowledge to pull Sheba closer to herself, but when she finds out that Sheba has not been completely truthful with her, Barbara lashes out with a lifetime of venom, blaming Sheba for making her do it. The secret comes out, and Sheba moves in with Barbara, marking for the elder lady the manifestation of all her fantasies: she is sharing a life with Sheba at last. However, there is a final trick in the deck to be played, and Sheba angrily confronts Barbara over everything that has occured between them; negating their close friendship to her efforts to be kind because no one else at the school even likes Barbara, and calls the older woman a vampire. In a manner of moments, Sheba causes the crashdown of all of Barbara's diary fantasies, and tells her point blank that things she wrote were not true or had never happened as Barbara described them.

Barbara is a vampire of sorts, in that she attempts to completely control the people she cares for, to keep them under her spell, and always keep them within arms reach. And despite the trickery, lying, and downright bitchiness of Dench's character in the film, I cannot help but feel pity for her at times. One sequence, showing Dench writing while in a bathtub, displays such a keen sense of the idea of lonliness bringing on a physical manifestation says so much about that chracter; this woman who has closed herself off emotionally from the rest of the world, only to let this one other woman get close to her, despite her fears. The fear of lonliness outweighs the fear of rejection, at least for Barbara.

Judi Dench is simply a marvel in this movie, and as she is not a likable character, one may be reluctant to tag her as the heroine of the piece. She is simply a one woman master class in the art of acting.